Exactly how and why Tom Waits made Swordfishtrombones three decades ago can only be understood by first heading even further back and attempting to piece together the man’s unlikely tectonic shift from cabaret to junkyard.

Forty years ago, the 23-year-old Tom Waits released his debut album, Closing Time. Spotted behind the piano by David Geffen in LA’s Troubadour less than a year earlier, he’d been snatched up, recorded, re-recorded, and ultimately fired directly into a jazzy songwriter-shaped hole in an industry already over-encumbered with singer-songwriters; each one just distinct enough to excuse their own disparate existence. Considering the colourful and enigmatic music that was to come from Waits in future years, Closing Time has always felt like something of a youthful misfire from an uncertain man. It set a precedent that was to dominate much of his work for the rest of the decade. His gradually boozier persona of the jazz club philosopher spent the remaining 70s touring, eating bad food and quietly churning out repetitive and derivative song writing that took aesthetic cues from the corner of Tin Pan Alley and Harlem. His idiosyncratic delivery and witty lyrics assured him a small but dedicated following, but by the time he reached the soundtrack sessions for Francis Ford Coppola’s One From The Heart in late 1980, we hear a man stuck in a feedback loop of self-parody, stuck out of place or time, and eternally bound to the smoke-filled jazz bars and diners, wry witticisms and Randy Newman-esque folk-form cadences upon which his career had been founded. Only on the near-atonal and darkly atmospheric One From The

Heart oddity, ‘You Can’t Unring a Bell’ is it possible to discern the faintest signpost of imminent sea change.

The Tom Waits of 1980 was not the musician worthy of discussion here today, and neither was he a man satisfied as an artist. Scattered across his canon up until this point there are a handful of small-scale experiments and diversions from his piano-driven schmaltz. ‘Diamonds On My Windshield’ from 1974’s The Heart Of Saturday Night had introduced the sugar-coated surrealism of Waits’ bass-heavy jazz-rapping, later revisited more fruitfully on Small Change with both ‘Step Right Up’ and ‘Pasties And A G-String’. Electric guitars drip fed into both Blue Valentine (1978) and more predominantly on Heartattack And Vine (1980), the former’s ‘Red Shoes By The Drugstore’ premiering the percussive bed that would eventually come to typify Waits’ looming industrial jazz bravado, and the latter audibly screamed for the singer’s dulling act to be revised. However, Tom Waits closed the decade unrelentingly married to the boozed romantic wit and comforting tropes of a predominantly nostalgic (albeit candid and often taboo) piano jazz singer.

Enter Kathleen Brennan.

"It was certainly not the first time that a relationship with a strong and well-organized woman has had that kind of effect on an artist’s life," says Mike Melvoin, keyboard player on The Heart Of Saturday Night (1974) and Nighthawks At The Diner (1975). But Melvoin also believes Brennan "put a stake through the heart of various things" in order to free Waits from his past.”

The above passage from Barney Hoskyns’ Low Side Of The Road, first extracted here on The Quietus back in 2009, encapsulates the importance of Brennan on his music and in particular Swordfishtrombones. The album had been many years in the making, swimming around in the back passages of Waits’ psyche, yet it was the catalyst of Brennan’s nurturing

influence that allowed Waits to put out his proverbial cigarette, roll up his sleeves and get to work. She was a script analyst, and Waits was in a Hollywood office writing songs for Coppola’s movie.

"I hatched out of the egg I was living in," he said, looking back on this time. "I’d nailed one foot to the floor and kept going in circles, making the same record."

Aside from the freeing nature of Brennan – who perhaps emancipated Waits’ from a decade of misinformed romantic longing – there were undoubtedly countless other vital influences and serendipitous changes in the singer’s life.

It’s safe to assume he discovered Captain Beefheart around this time – who was just releasing his harshest and most alien swansong, Ice Cream For Crow. In fact, it’s a moot point as to whether or not it was Brennan who switched Waits on to the Captain. Furthermore, the influence of seminal wanderer-cum-composer Harry Partch is indisputably present on Swordfishtrombones. Thus the presence of Waits’ old friend and member of the early-80s incarnation of the Harry Partch Ensemble, Francis Thumm, was clearly another vital driving factor in his transformation. Thumm – with whom Waits purportedly had been privately making music since first meeting in 1969 – acted under the ever mysterious label of ‘arranger’ on Swordfishtrombones, while also providing the sort of unusual and exotic instrumental accompaniment (he’s credited with ‘glass harmonica’ and ‘metal aunglongs’ on the album) beloved to the deceased Partch – the composer had regularly adapted and invented his own microtonal instruments especially for his compositions as far back as the 1930s.

The unlikely mentor of Harry Partch’s ghost ultimately proves a befitting one. In 1930 Parch destroyed all of his previous compositions, and in 1935, he began to live out his overarching rejection of the destructive power of cultural conformity, and abandoned a promising future as a composer and musicologist to live as a hobo and drifter across America during the height of the Great Depression. Nine years of train hopping and note-taking followed, and his decision to mature into a life of rough sleep and true grit was one later echoed by Waits’ early-80s aesthetic turning point.

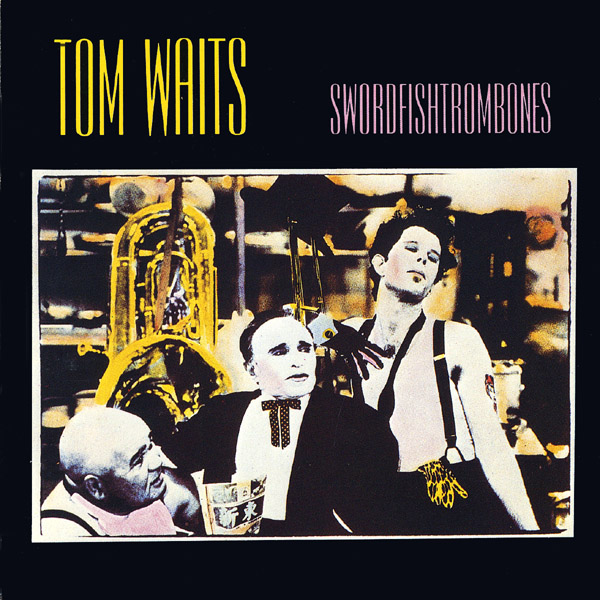

Swordfishtrombones is not an influential album in the strictest sense. It did little to expand the aural palettes of popular music, it triggered no major movement to speak of, and if anything lost Tom Waits a sizeable chunk of his own dedicated (if rather dull) following. However, it’s also a near perfect masterpiece; a 40-minute magical realist portrait of the human condition, and a missive from a sonically parallel universe. Its most lasting impact has most certainly been on Waits himself, for whom it represents both the high point and fulcrum of his entire career. The songs, instrumentals and monologues that lie therein paint a Brueghelian picture of an underground world of misfits and freaks, massively darker and more compelling than the jazz cafes of his previous work. If Small Change sounded like Woody Allen’s Annie Hall, then Swordfishtrombones is Tod Browning’s Freaks (which also, and far more literally, inspired the album’s iconic mutant cover art by Michael A. Russ).

The first two tracks both open with brief descending figures, dimly bugling the album’s overarching theme of descent into the opening track’s titular ‘Underground’, which – as an opening statement – summarises the album perfectly.

Swordfishtrombones is essentially composed of fifteen differing and yet related vignettes, detailing fifteen disparate tales from the real world. Servicemen’s tales crop up most often, whether it’s a letter home from the dank streets of Hong Kong (‘Shore Leave’), a veteran’s descent into madness upon the unwelcome return to reality (‘Swordfishtrombone’) or an itinerary from the treasure chest of an old war hero (‘Soldier’s Things’).

Elsewhere Waits’ weary eyes fall on banality of small town life, highlighting a murky Australian ‘Town With No Cheer’, and the previously unsung images from life in the suburbia of Frank Capra’s America (‘In the Neighbourhood’).

Most telling is perhaps the mighty ’16 Shells From A 30.6’, a tale of a bounty hunt in turn of the century America, which unsubtly mentions making “a ladder from a pawn shop marimba”, aggressively parodying Waits’ own victorious battle with either his own inability to deliver as an artist, or more literally a fight with labels and producers.

Musically, the album hops timbres and styles as often as it does character or setting. ‘Underground’ is a sick reimagining of a Slavic march, while ‘Down, Down, Down’ and ‘Gin Soaked Boy’ are both the work of some only slightly twisted version of a dime-a-dozen blues band. ‘Shore Leave’ is perhaps the most Partchian offering. Listen to CRI’s release of several homemade Partch recordings dating from the tale end of the 1940s. Partch’s near-atonal bass marimba setting for spoken lyrics extracted from African-American novelist, Willard Motley’s Knock On Any Door (aptly entitled ‘The Street’) almost sounds like some childish demo tape for Waits’ ‘Shore Leave’.

“Over the jail the wind blows, sharp and cold. Over the jail and over the car tracks the cold wind blows. The streetcar clangs east, turns down Alaska Avenue”

The patchwork of styles assimilated into Swordfishtrombones does contain a handful of unifying threads. The sounds of brass are dotted across the record, drifting across the background of ‘16 shells’’ unrelentingly brash beat and only coming, and playing the part of the town brass band on ‘Neighbourhood’. Waits regulars Greg Cohen (later in various incarnations of Zorn’s Masada projects) and Larry Taylor (Canned Heat) prove powerful double bass foils, bedding the various worlds of Swordfishtrombones with a signature growl to match Waits.

Most vital however, is (unsurprisingly) the voice of Waits, which had never been as chameleonic. He whispers, yells, croons and yearns across the record. He’d always been a character actor, but never with as much breadth.

Halfway through the album’s first side, we witness what seems to perhaps be the man’s only recorded moment out of character. ‘Johnsburg, Illinois’ strips back to the basics of piano, bass and voice, while Waits – mostly devoid of his usual roughness – sings in heartfelt and honest tribute to his then new wife (the title refers to her birthplace). Less than eight years earlier, Waits had been in character for Nighthawks At The Diner, comically poking fun at marriage on ‘Better Off Without a Wife’.

Ultimately, Swordfishtrombones would form the opening part of a trilogy as formulated by Waits after the fact. Rain Dogs and Franks Wild Years both had much of the same variety of instrumentation and dark take on Americana that built Swordfishtrombones, but never again would Waits find such a perfect balance between his dramaturgy and his ability to hone in on the bizarre tales that go unheard deep within the cracks of society Swordfishtrombones was a cul-de-sac that Tom Waits only walked the once, but it’s still a landmark achievement, and an inspiring departure from the man’s early work.

Wherever bizarre, deep and dark lives go unsung, the spirit of Swordfishtrombones lives on.